Write a Theme About the Maus by Art Spiegelman

E arly in the 2nd book of Maus – the graphic novel about the Holocaust that made Art Spiegelman's reputation – he includes a passage showing the reaction to the publication of volume one. The creative person is sitting at his cartoon board, perched atop a mountain of dead bodies, equally a succession of importunate reporters oversupply in bombarding him with questions: "Okay... let'southward talk about State of israel..." "Could you lot tell your audience if drawing Maus was cathartic? Do you experience better at present?"

As the questions come up in, he struggles to respond – "A bulletin? I dunno..." "Who am I to say?" – and over the course of the post-obit panels shrinks to the size of a toddler, marooned in his writing chair. "I want... ABSOLUTION. No... No... I want... I desire... my MOMMY! WAH!" The reporters vanish, and mini-Spiegelman confesses: "Sometimes I simply don't feel like a functioning adult."

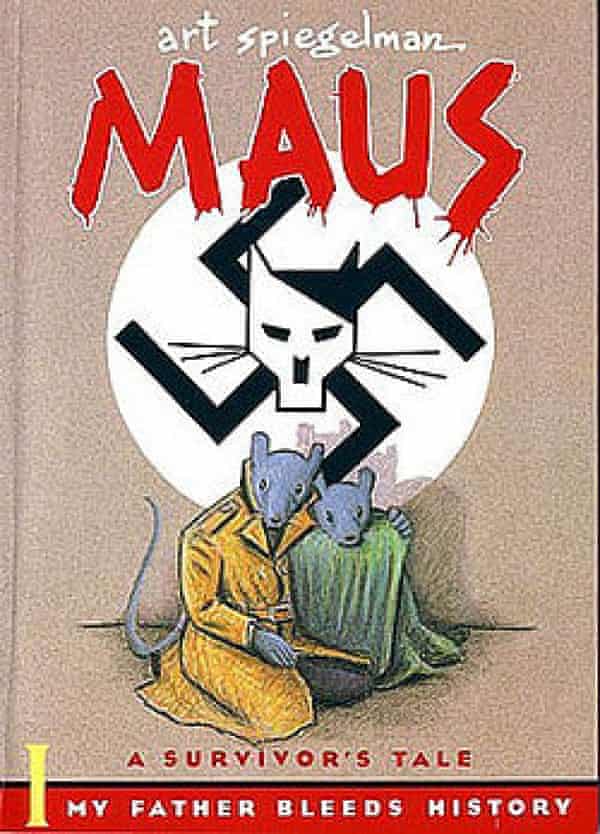

Notwithstanding existence adult is, in a way, what Spiegelman is famous for. In the historic period-one-time give-and-take about when comics finally "grew upwards" Maus is often exhibit A. The New Yorker called it "the get-go masterpiece in comic-book history". It'southward the comic that people who don't read comics have read, and the only graphic novel e'er to take won a Pulitzer prize. Xl years on – the offset chapter appeared in series form in Spiegelman'southward secret zine Raw in December 1980 – it remains a monument in the genre.

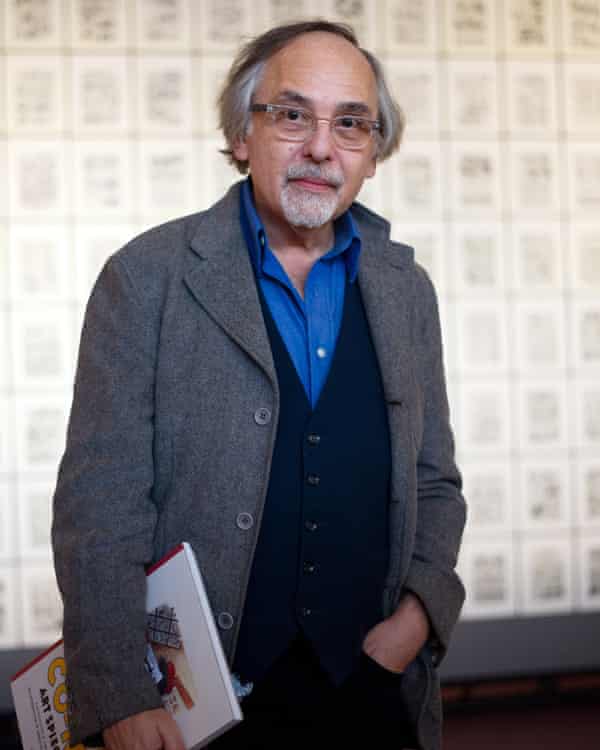

I talk to Spiegelman over Zoom from his New York apartment. Wearing a pale fedora and tinted spectacles indoors and choffing on a vape, he's fidgety and garrulous and emphatic. But when I mention the anniversary he'south vague. "There seems to exist some other anniversary bachelor from anything to anything if ane merely finds the correct two events."

Its creator may be vague, but Maus is precise. It's a complex and subtle piece of work: partly a family memoir, partly an act of historical documentation and (as the passage I describe above makes clear), partly a self-cogitating account of its ain cosmos. The frame story, set in late 1970s New York, shows the grown-upwards Spiegelman's relationship with his grouchy and eccentric elderly father Vladek, and his attempts to interview him about his early on life. Threaded through this is the account that emerges of Vladek's human relationship with Spiegelman's mother (who took her own life in 1968, when Art was but emerging from his teens), the Nazis' rising to power, and the road to Auschwitz.

Information technology'south a paradoxical mixture of apparent extravaganza and farthermost fidelity to the truth. In the historical sections Germans are drawn every bit man-bodied cats, and Jews as mice, and in some of the present-day story the protagonists wear mouse masks. Still their wording – the cadences of his Polish-born father's English, his kvetching and kibitzing – is impeccably rendered, and Spiegelman worked similar crazy to verify the historical detail, downward to the look of the machinery in the can-shop in which his male parent worked.

At one indicate in the book, Spiegelman is in despair: "I feel then inadequate," he tells his wife, "trying to reconstruct a reality that was worse than my darkest dreams. And trying to do it as a comic strip! I guess I fleck off more than than I can chew." He didn't, patently: but it's surprising that a lifelong champion of the comic strip as an expressive medium seemed to be saying there that some subjects might be out of its accomplish.

"I didn't mean comics," he says now. "I meant fine art or literature. I didn't feel information technology was possible to give structure to this that would be meaningful. I didn't know how to proceed in making it in comics form, considering in that location wasn't much of a model for making something like it. Simply I think if I had somehow gone down one of those cord theory universes next door where I became a writer, I would have the same misgivings."

Spiegelman'south success had the disconcerting outcome of placing an artist who had been happy in the comix-with-an-x cloak-and-dagger – a lysergic disciple of R Crumb – very firmly in the literary establishment. He became a staple of Tina Brown's New Yorker, a darling of academics, and came to exist regarded by many, not without resentment, as a sort of capo of the Usa comics scene.

"I remember when I first got this Pulitzer prize I thought it was a prank telephone call," he says, "Just immediately after I got dorsum to New York, I got an urgent phone call from a wonderful cartoonist and friend, Jules Feiffer: 'We take to meet immediately. Can you come out and accept a java?' And we met. He said: 'You have to understand what you've just got. It's either a licence to impale, or something that will kill you.'"

That comics are now considered "respectable" – thanks in function to Maus – is something Spiegelman never quite looked for. But he acknowledges information technology has its advantages. "I'm astounded past how things take inverse. And I would say I might have been dishonest or disingenuous when I said I wasn't interested in it beingness respectable. I love the medium. And I dear what was washed in it from the 19th century to at present. But I know that on some level, I desire it to be able to non take to make everything have a joke, or an escapist take chances story."

His rocket launch into canonicity was both "liberating and also incredibly circumscribed – trying to find places to become where I wouldn't have to exist the Elie Wiesel of comic books". Fifty-fifty at the fourth dimension, Spiegelman seems to have been conscious that Maus would be in danger of defining him. The next projection he took on was illustrating Moncure March'southward jazz-historic period poem The Wild Party for a small press: "This was going to be a kind of polar opposite [to Maus]: decorative, erotic, frivolous in many ways and involved with the pleasures of making; although information technology didn't turn out to be and so pleasurable in its third year. Every projection I outset turns into a bury."

And withal, what coffins. Spiegelman'due south attention to his arts and crafts, to the grammar of comics and their narrative possibilities, is formidable. Information technology seems quite in keeping that an apparently unproblematic illustration projection turned into a 3-year job. Maus took more a decade to complete – "I always assumed it would have about two years" – and in conversation he will zero in on the tiniest details in individual panels from memory. There's a unmarried transition panel, for instance, where a train ticket goes in equally the explanation, that he identifies as having been fatigued under the influence of Will Eisner's The Spirit.

In an afterword to Breakdowns, an anthology of his earlier work, Spiegelman writes of his younger cocky: "In an hole-and-corner comix scene that prided itself on breaking taboos, he was breaking the one taboo left continuing: he dared to call himself an artist and call his medium an art-form." But that aspiration doesn't mark a straightforward high culture/low culture separate.

"Lower middle class to middle class in terms of my upbringing," Spiegelman says, "I was very suspicious of high culture and kind of described myself as a slob snob. If it wasn't printed on newsprint, the hell with it. If I was learning well-nigh modernism, it was more likely to be from Winsor McCay and George Herriman than from Picasso. I was resistant. I read Kafka [and thought] he would have been a good script author for The Twilight Zone. I was seeing it equally a zone of civilization that wasn't exactly loftier or low, that just had to do with culture I could use."

A thunderbolt moment was his discovery of Harvey Kurtzman and Mad magazine: "That was what changed my life," he says. "I guess Mad came out equally the everyman of low civilisation, just it actually has become our culture. The irony, the self-reflexivity, the questioning, the parodic enveloping of everything seen through that lens." The recent demise of the print magazine was, he says, "mission accomplished. Yous know, in that location wasn't much more than it could do."

And he is startlingly protean as a creator. A console of Chris Ware or Daniel Clowes, Herriman, Bill Sienkiewicz or Jack Kirby is instantly identifiable as such. But you lot'd struggle to look at the urbane images for The Wild Party, or his psychedelic early piece of work at Raw, or the cross-cutting of styles in In the Shadow of No Towers, and instantly clock them as the work of the author of Maus. And he still has people approaching him in astonishment to discover he was also the creator of The Garbage Pail Kids, the trading cards of 1980s playground fame. "It'due south kind of dissonant for people," he says. He is, as was said of the belatedly Clive James, "a brilliant bunch of guys".

"That's prissy phrasing," he says. "I took to heart a quote from Picasso: 'Style is the difference between a circumvolve and the mode you lot depict it.' I would like to call back of myself equally simply using whatever way seems appropriate to the work, and the style is as much finding out what the work is as the work itself. Everything I've done comes later a lot of stylistic inquiry. And the main matter that makes it my fashion is I but depict desperately." That's not wholly cocky-deprecation. When he's tried writing for others to describe, he says, "I would find that other people couldn't draw it incorrect the correct manner."

Incorporated into Maus is a total reprint of his short strip "Prisoner on the Hell Planet", which describes his nervous breakup in the backwash of his mother'southward suicide in a vividly expressionist idiom (and which portrayed Spiegelman wearing the striped pyjamas and striped cap of an Auschwitz inmate). Ane reason he did that, he says, is that the fact of his ain breakdown "needed to exist entered into the deposition", just the other was something necessary "formally – which was to show that the cartoon style in Maus was a decision".

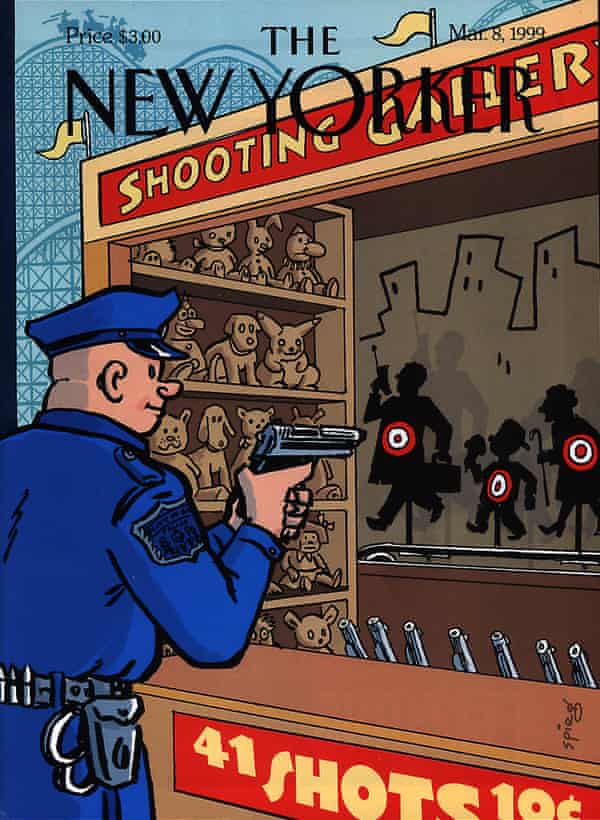

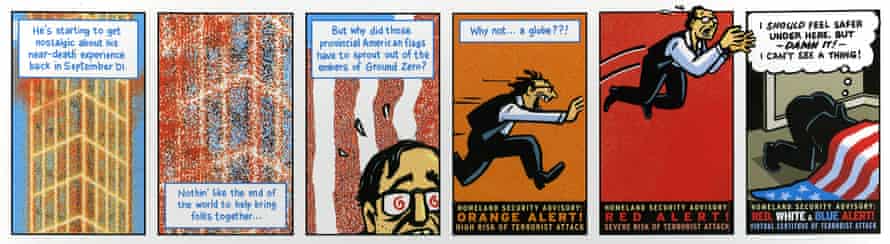

His i major foray into cartooning the political moment also had a drastic stylistic upshot. In the Shadow of No Towers charted his response to 9/11, and found him out of kilter non only with his countrymen (David Remnick'southward New Yorker declined to publish a comic whose author was "equally terrorised by al-Qaida and my authorities") but with himself. "I remember Towers came close to the whatever-port-in-a-storm kind of driving through a hurricane," he says. "The styles shifted from sequence to sequence and panel to panel. And that felt very correct for trying to deal with the fragmentation that nine/11 caused for me. And I remember that'due south kind of where I'm at now."

Indeed, he delayed this interview for several weeks as he attempted to process the summer's chaos. "I am really trying to sympathize what the fuck?" he says. "The globe was never a bed of roses, but at this signal, every fourth dimension I await up, it'southward like … oh, man, you know? I feel like if I had a tattoo – which I'll never get voluntarily – information technology would exist on my chest. It would say: 'Y'all can't make this shit up', and information technology would glow vivid ruby about five times a mean solar day." Merely he says he has no impulse to answer to America'due south electric current turmoil in art.

"Early on on I realised I didn't want to become a Trump caricaturist – that it was just playing into his narcissism, ultimately. I just backed off and I'm now trying to encounter what the hell's been happening to us. Information technology makes me recant something I rather cockily said back in 2001, which was when I found myself unable to move from September xi to September 12. About three months after, my brains poured dorsum in my head and I said: 'I guess disaster is my muse.'" He recants: "Now disaster is just a fucking disaster."

And in a sense, that was the theme of Maus – amid whose many scrupulousnesses was a faithful rendition of the extremely hard and annoying personality of Vladek. "I thought it was important to show that there's nothing ennobling virtually being victimised," Spiegelman says. "That's a very Christian concept. But people don't come out of it as better humans: they just come out of it seared, scarred. She came out with so much wisdom, or he came out as stupid equally he went in, he came out fifty-fifty more traumatised and befuddled than when he went in. Information technology's a spectrum. But what it is, is: it wasn't the best who survived, and information technology wasn't the worst. It was random."

-

In the Shadow of No Towers by Fine art Spiegelman (Penguin Books, £forty). To order a copy get to guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2020/oct/17/graphic-artist-art-spiegelman-on-maus-politics-and-drawing-badly

Post a Comment for "Write a Theme About the Maus by Art Spiegelman"